Erdoğan Leads Turkey to the Precipice

by Daniel Pipes

Australian

[N.B.: The Australian's title is "Would-be dictator Erdogan leading Turkey to the precipice" and its version uses Australian spelling]

The Republic of Turkey is undergoing possibly its greatest crisis since the founding of the state nearly a century ago. Present trends suggest worse to come as a long-time Western ally evolves into a hostile dictatorship.

The crisis results primarily from the ambitions of one very capable and sinister individual, Turkey’s 61-year old president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. A career politician who previously served four years as the mayor of Turkey’s megacity, Istanbul, and then eleven years as the country’s prime minister, he forwards two goals hitherto unknown in the republic: dictatorship and full application of the Shari’a, Islam’s law code.

During his first eight years of power, 2003-11, Erdoğan ruled with such finesse that one could only suspect these two aspirations; proof remained elusive. This author, for example, wrote an article in 2005 that weighed the contradictory evidence for and against Erdoğan being an Islamist. A combination of playing by the rules, caution in the Islamic arena, and economic success won Erdoğan’s party, Justice and Development (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, or AKP), increasing percentages of the vote in parliamentary elections, going from 34 percent in 2002, to 46 percent in 2007, to 50 percent in 2011.

That 2011 election victory, his third in succession, gave Erdoğan the confidence finally to remove the armed forces from politics, where they had long served as Turkey’s ultimate power broker. Ironically, this change ended the increasing democratization of prior decades for his fully taking charge allowed Erdoğan to develop an oversized ego, to bare his fangs, flex his despotic muscles, and openly seek his twin objectives of tyranny and Shari’a.

Indeed, Erdoğan made his power felt in every domain after 2011. Banks provided loans to the businessmen who kicked back funds to the AKP. Hostile media found themselves subject to vast fines or physical assault. Ordinary citizens who criticized the leader found themselves facing lawsuits, fines, and jail. Politicians in competing parties faced dirty tricks. Like a latter-day sultan, Erdoğan openly flouted the law and intervened at will when and where he wished, inserting himself into legal proceedings, meddling in local decisions, and interfering with police investigations. For example, he responded to compelling raw evidence of his own and his family’s corruption by simply closing down the inquiry.

The Doğan group, publisher of Hürriyet (pictured here) was hit wth a US$2.5 billion fine in 2009. The Doğan group, publisher of Hürriyet (pictured here) was hit wth a US$2.5 billion fine in 2009. |

The Islamic order also took shape. School instruction became more Islamic even as Islamic schools proliferated, with the number of students in the latter jumping from 60,000 to 1,600,000, a 27-fold increase. Erdoğan instructed women to stay home and breed, demanding three children apiece from them. Burqas proliferated and hijabs became legal headgear in government buildings. Alcohol became harder to find and higher priced. More broadly, Erdoğan harked back to the piety of the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922), eroded the secular republic founded in 1923 by Kemal Atatürk, and positioned himself as the anti-Atatürk.

Erdoğan also faced some serious problems after 2011. The China-like economic growth slowed down and debt spiraled upwards. A disastrously inept Syria policy contributed to the rise of the Islamic State, the emergence of a hostile Kurdish autonomous area, and millions of unwelcome refugees flooding into Turkey. Foreign relations soured with nearly the entire neighborhood: Tehran, Baghdad, Damascus, Jerusalem, Cairo, Athens, the (Greek) Republic of Cyprus, and even (Turkish) northern Cyprus. Ties also went south with Washington, Moscow, and Beijing. Good relations were limited to Doha, Kuala Lumpur, and – until recently, as shown by the many indications of Turkish state support for the Islamic State – Raqqa.

Erdoğan has pugnaciously responded to this predicament by stating, “I do not mind isolation in the world” and even to suggest that other leaders were “jealous” of him. But he fools no one. The old AKP slogan of “Zero problems with neighbors” has dangerously turned into “Only problems with neighbors.”

If Erdoğan’s base loves his strongman qualities and stands by him, his aggressive actions and policy failures cost him support, as major blocs of voters rejected him, especially Kurds (an ethnic minority), Alevis (a religious community spun off from Islam), and seculars. The AKP’s vote dropped accordingly from 50 percent in 2011 to 41 percent in the June 2015 elections, a reduction that meant its losing a long-standing majority in parliament and the numbers to govern on its own.

The poor showing in June 2015 blocked Erdoğan from legitimately gaining his dream powers as executive president. But being the politician who stated long ago, when mayor of Istanbul, that democracy is like a trolley, “You ride it until you arrive at your destination, then you step off,” he predictably did not let something as petty as election results get in his way. Instead, he immediately began scheming to get around them.

He opted for a pair of tactics: First, he rejected power sharing with other parties and called another election for Nov. 1; in effect, he offered Turks another chance to vote as he wanted them to. Second, after years of negotiating with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê, or PKK), Turkey’s leading Kurdish violent insurgent group, he renewed war on it. In doing so, he hoped to win over supporters of the anti-Kurd ethnic Turkish nationalist party, Nationalist Action (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi, or MHP).

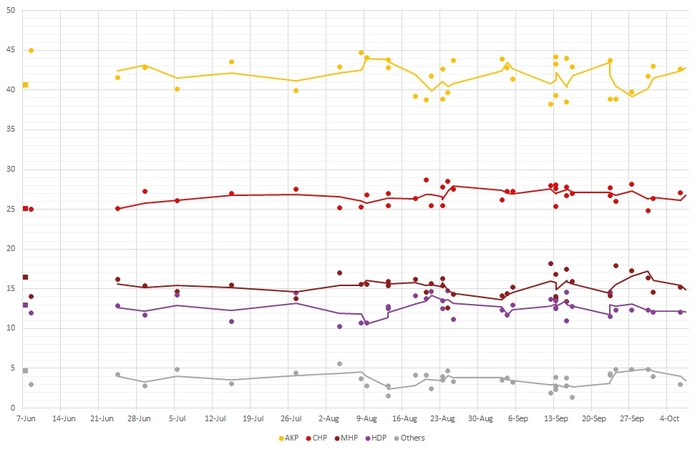

These tactics appear to be futile; polls show the AKP losing as many Kurds as it gains Turkish nationalists, and so likely to fare in November about the same as it did in June. But the tactics are highly consequential, tearing apart the body politic, creating tensions and prompting violence. The current round began in July with the bombing of peace marchers leaving 33 dead, followed by PKK retaliation against representatives of the state, a Kurdish town placed under siege, and twin bombings in the capital Ankara (widely considered ultimately attributable to Erdoğan) which killed 105 peaceful protestors. And yet two weeks remain before voting day …

Polls of Turkish voters since the June 7, 2015 elections. Polls of Turkish voters since the June 7, 2015 elections. |

In other words, Erdoğan’s obsession to win a parliamentary majority is doing fundamental damage to the country, damage that takes it to the precipice of civil war.

What makes the situation slightly absurd is that, whatever the results of the Nov. 1 election, Erdoğan will doggedly continue his campaign to become dictator. If he cannot do so legitimately, he will do so illegitimately. Repeating what I wrote just before the June election, “how many seats the AKP wins hardly matters. Erdoğan will barrel, bulldoze, and steamroll his way ahead, ignoring traditional and legal niceties with or without changes to the constitution. Sure, having fully legitimate powers would add a pretty bauble to his résumé, but he’s already the tyrant and Turkey’s course is set.”

Assuming the AKP does not win the votes necessary to make Erdoğan a legal strongman, how might he manage this illegally? The past year, since he became president, offers a hint: Erdoğan has bleached the once-powerful prime minister’s office of its authority. In all likelihood, he will extend this process to the rest of the Turkish government by setting up an alternative bureaucracy in his huge, new presidential palace, with operatives there controlling the ministries of state. An apparently unchanged formalistic structure will take orders from the palace autocrats.

Likewise, the parliament will remain untouched in appearance but voided of true decision making. Civil society will also find itself under palatial control as, exploiting his financial and legal levers, Erdoğan shuts down publicly dissenting voices in the judiciary, the media, the academy, and the arts. In all likelihood, private dissent will next be proscribed, leaving Padishah Recep I master of all he surveys.

What will he do with this authority? In part, he will exult in it, in the unbridled range of his ego and his writ. Beyond that, he will use this might to advance his Islamist agenda by harking back to the Ottoman imperial legacy, further undoing the Atatürk revolution, and imposing Sunni Islamic laws and customs. Just as autocracy came to Turkey in tranches, so will Shari’a be implemented piecemeal over time. The processes already underway – Islamic content in schools, women urged to stay home, alcohol disappearing – will continue and accelerate.

Assuming that Erdoğan’s mystery diseases stay under control, this Islamist idyll contains just one flaw: foreign relations, the most likely cause of its demise. Unlike a fellow dictator like Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, who had the good fortune to rule in the placid confines of South America, Erdoğan is surrounded by the world’s most crisis-ridden region. His domestic success increases the chances of an ego-driven blunder that diminishes or ends his rule. Tense relations with Iran and Russia over the fighting in Syria offer one temptation, as the seemingly purposeful Russian penetrations of Turkish airspace highlight; or with Israel over Jerusalem or Gaza; or with Cyprus over the newly discovered gas fields.

(With this prospect presumably in mind, Erdoğan’s son Bilal recently relocated to Bologna, Italy, supposedly to work on a Ph.D. thesis; a whistleblower plausibly claims Bilal from there will manage the family’s vast fortune.)

When the Erdoğan era expires, the country will be much more divided than when it began in March 2003 between Turk and Kurd, Sunni and Alevi, pious and secular Sunnis, and rich and poor. It will contain millions of difficult to assimilate Syrian refugees and Kurdish areas declared independent of the state. It will be isolated internationally. It will contain a hollowed-out government structure. It will have lost the tradition of legal impartiality.

Erdoğan’s larger accomplishment will have been to reverse Atatürk’s Westernizing policies. Whereas Atatürk and several generations of leaders wanted Turkey to be in Europe, Erdoğan brought it thunderingly back to the Middle East and to the tyranny, corruption, female subjugation, and other hallmarks of a region in crisis. As Turks struggle over the years to undo this damage, they will have ample opportunity to ponder the many evils bequeathed them by Erdoğan.

Mr. Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes) is president of the Middle East Forum. © 2015 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

Related Topics: Turkey and Turks

receive the latest by email: subscribe to daniel pipes’ free mailing list

This text may be reposted or forwarded so long as it is presented as an integral whole with complete and accurate information provided about its author, date, place of publication, and original URL.